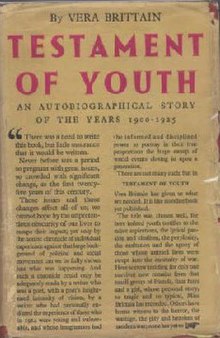

During the commemorations for the centenary of the First World War last month I decided that I should re-read Vera Brittain's memoir Testament of Youth sooner rather than later. There was, of course, the usual trepidation one feels when approaching a book one first read as a teenager, but I am happy to say that it has more than held up to my memory of it as a magnificent book. Vera Brittain left Somerville College, Oxford after one year to serve as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse (or VAD) during the war and the book covers her life from her birth in 1893 until 1925, when she married. Testament of Youth is particularly valuable in giving an impression of the state of mind of the British in the run up to the war, throwing some light on why it was such a cataclysmic event and so very shattering to those who lived through it.

The first clue to this is given in the preface written by her daughter, the politician Shirley Williams, who writes that one reason we are so haunted by the war is, "the total imbalance between the causes for which the war was fought on both sides, as against the scale of the human sacrifice". Brittain's account of the parts of the line, in the early part of the war, where neither side could see the point in killing one another and so had a small voluntary truce, shooting into the air and no man's land, is just one illustration of this point. Why this war in particular has caught our collective imagination and is such an important part of our collective story is a question I have often pondered. Our collective remembrance of war is still, a century on, so strongly shaped by the First World War, with our Remembrance Day poppies and our misty-eyed reading of Rupert Brooke and "age shall not weary them".

Brittain's book is a true help to understanding this question, by providing a solid pre-war background she is able to show how shattering the war was to her generation. There seems to have been a deep complacency and belief in progress, running alongside a belief in the spiritual good of war, testing us and even (in a way that would seem shocking to a post-1945 audience) purging the population. Brittain's account of attending speech day at her brother's public school in July 1914, with its military manoeuvres, shows the incredible militarism of the pre-war public schools, whence came most of the politicians and leaders of Britain. The Arnoldian* curriculum of Officer Training Corps, sport and extensive study of Classics** lent itself to a romanticised, spiritual view of war; it is after all a small leap from the Pass at Thermoplyae to the poetry of the early part of the war. However, these ideals failed to live up to the realities of trench warfare where death came at random from a shower of shells and bullets, killing indiscriminately the strong with the weak.

Testament of Youth has more than lived up to my teenage memories, it is an epic read, but not only is it worth reading, it is engrossing, so that you do not realise that you have somehow read a hundred, or two hundred pages. According to the biography of Brittain at the beginning of Testament of a Generation (a collection of her and Winifred Holtby's journalism) she found the book extremely hard to write, but I am immensely glad she persevered. I cannot recommend this book enough, do go and read it, it will enrich your understanding of the First World War immeasurably, but you will also spend time in splendid company.

Incidentally, reading Testament of Youth alongside Testament of a Generation has provided an interesting counter-point and each has cast some light on the other. Aside from the impression that feminism has not advanced that far from the 1920s and that in politics little changes, each book has provided flashes of insight that have illuminated aspects of one another. I was particularly interested to read an article discussing, in 1929, calls for the abolition of Remembrance Sunday, some apparently feeling that 11 years was quite sufficient to have remembered the war. Likewise her horror at finding her children's nanny fixing a poppy on baby Shirley's cot for Remembrance Day throws light upon the gulf Brittain felt between her generation and the one that followed it; for her the poppy was a symbol of war and grief, but for her young nanny it was another "flag day" like any other.

You can see the rest of The Year in Books entries here

*Dr Arnold of Rugby School, whose reforms set the pattern for public schools in the 19th century and whose influence is still felt today, cf. Tom Brown's School Days

**Many of the texts studied were decidedly martial in flavour such as Homer, Thucydides and Caesar

Showing posts with label women. Show all posts

Showing posts with label women. Show all posts

Monday, 29 September 2014

Sunday, 29 June 2014

The Year in Books: June

This month's choice was something of an epic, The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing, I listened to all 27 or so hours of it on audio book in May and June. However, at no point was listening a slog, rather like a long, enjoyable journey; Juliet Stevenson's brilliant reading was a vital part of the experience. The story concerns Anna, a divorced writer of a best selling novel in her 30s living in London with her daughter and covers a period of time from the 1930s to the 1950s. In its structure it is far from a "normal" novel though, it moves fluidly through time and through different narrative perspectives and is a master class in plot and potentially unreliable narration. The facts of who is who, or why or how particular things have happened are not spelt out, instead the reader is left to put the pieces of the jigsaw together. Although this sounds as though it could be infuriating, I found that it actually meant that I thought a lot about the novel as I went along and tried to fit the pieces together, some you are never openly told but are simply expected to put together. You are quite simply plunged into Anna's world.

The Golden Notebook is very much a novel of the inner life and is mostly told through a first person narrative, except when Anna is looking at the content of the notebooks into which she has attempted to divide up the various strands of her life. One of these is a third person account of her time in Africa during the second world war and her experiences involved with the Communist party there, for this section of the book Anna gives herself a new name, Ella and also renames most of the other protagonists of the novel. Hence Lessing is able to leave you unsure how accurate this account of the past is, as Anna tries to create a distance between herself and her past and to examine it in a new way and try out new scenarios - Ella has a son, whereas Anna has a daughter for example.

Relationships and sex play a large part in the novel, as Anna and her friend Molly seek to find a new way to live as single women, a process which seems to result in a lot of unsatisfactory affairs, generally with married men, who seem to see them as available. In this respect Doris Lessing gives a very different perspective on the life of the unmarried woman in 1950s London to that of another of my favourite novelists, Barbara Pym, whose women are solidly respectable, generally engaged in unrequited love, the church and lonely meals for one in small flats. Anna's life seems to demonstrate the beginnings of the women's liberation movement of the 1960s, its foundations, while Barbara Pym documents the last of a fast fading world. Maternity becomes another key theme as Anna brings up her daughter, a very conventional young girl and Molly struggles with her son and what he should do with his life. Molly's former husband Richard, who had a brief involvement in Communism, but has now settled down to business, represents conventionality and money and Tommy, their son, seems caught in between their two ways of life. Furthermore one gets the impression from The Golden Notebook that it is not only the women who are struggling to sort out their relationships but the men too, such as Molly's ex-husband Richard, who moves from his second to third wives as the novel progresses.

Anna and her friends are experimenting in new ways of living, not just in terms of relationships but in everything; the Communist Party, in which many of the characters have been or are involved in, is a part of this search. In the earlier, African part of the novel, Anna and her friends are frenetically engaged with the Communist Party and taking on some of the racism of the British rule. While later on the novel illuminated the impact of the USSR upon the wider Communist Party, in particular showing the impact of Stalin's death and the revelations of atrocity that followed it on communists outside Russia; for many it seemed to destroy their faith in communism. At the same time Anna comes into contact with Americans exiled because of the MacCarthy era in American politics; injustice in its various forms is a great concern of the novel.

Therefore, amid this tumult of ideas and identities, it may come as little surprise that mental health is another important strand of the novel, both for Anna and for those around her. As I had been thinking a fair amount about identity myself before beginning this novel I did find it fascinating; there were a number of those moments of recognition when a novel describes a thought, a feeling, a sensation and you realise that you are not alone in what you feel. Doris Lessing's descriptions of Anna's sessions with her therapist and of her time of disintegration, are vivid and the latter time becomes immersive, drawing you into Anna's world, it is powerful writing. While Anna's notebooks, culminating in the final golden notebook of the title, are her way of working out her own identity and what she should do next, having published this successful novel and had a long, ultimately unsuccessful affair.

I have written all this and yet hardly touched on the themes, ideas and people of this novel, nor done the novel remote justice. The Golden Notebook has to be one of the most thought provoking, absorbing books I have read in years and although its length may seem daunting at first I would recommend making the effort. As time went on I found that I could lose hours to the book and that I became deeply engaged with what happened to Anna and loved the "Londonness" of the book - certain writers capture London so well. While doing a little research to write this I have found The Golden Notebook Project, a website containing the novel and the debate a number of female writers are carrying on in the margins, with space for further debate in a forum, which might be an interesting way of reading it. Lessing's own preface is on there too, although I am glad that I had not read it before I tackled the book, I prefer to make my own impressions, then read the introduction or preface to novels. The audio book I listened to is available for download here - it is very much cheaper if you join Audible and buy some credits - and I very much recommend the reading, an excellent option for knitters or other crafters.

Perhaps this coming month I will read something that does not concern feminism?

All the other posts from A Year in Books can be viewed here

The Golden Notebook is very much a novel of the inner life and is mostly told through a first person narrative, except when Anna is looking at the content of the notebooks into which she has attempted to divide up the various strands of her life. One of these is a third person account of her time in Africa during the second world war and her experiences involved with the Communist party there, for this section of the book Anna gives herself a new name, Ella and also renames most of the other protagonists of the novel. Hence Lessing is able to leave you unsure how accurate this account of the past is, as Anna tries to create a distance between herself and her past and to examine it in a new way and try out new scenarios - Ella has a son, whereas Anna has a daughter for example.

Relationships and sex play a large part in the novel, as Anna and her friend Molly seek to find a new way to live as single women, a process which seems to result in a lot of unsatisfactory affairs, generally with married men, who seem to see them as available. In this respect Doris Lessing gives a very different perspective on the life of the unmarried woman in 1950s London to that of another of my favourite novelists, Barbara Pym, whose women are solidly respectable, generally engaged in unrequited love, the church and lonely meals for one in small flats. Anna's life seems to demonstrate the beginnings of the women's liberation movement of the 1960s, its foundations, while Barbara Pym documents the last of a fast fading world. Maternity becomes another key theme as Anna brings up her daughter, a very conventional young girl and Molly struggles with her son and what he should do with his life. Molly's former husband Richard, who had a brief involvement in Communism, but has now settled down to business, represents conventionality and money and Tommy, their son, seems caught in between their two ways of life. Furthermore one gets the impression from The Golden Notebook that it is not only the women who are struggling to sort out their relationships but the men too, such as Molly's ex-husband Richard, who moves from his second to third wives as the novel progresses.

Anna and her friends are experimenting in new ways of living, not just in terms of relationships but in everything; the Communist Party, in which many of the characters have been or are involved in, is a part of this search. In the earlier, African part of the novel, Anna and her friends are frenetically engaged with the Communist Party and taking on some of the racism of the British rule. While later on the novel illuminated the impact of the USSR upon the wider Communist Party, in particular showing the impact of Stalin's death and the revelations of atrocity that followed it on communists outside Russia; for many it seemed to destroy their faith in communism. At the same time Anna comes into contact with Americans exiled because of the MacCarthy era in American politics; injustice in its various forms is a great concern of the novel.

Therefore, amid this tumult of ideas and identities, it may come as little surprise that mental health is another important strand of the novel, both for Anna and for those around her. As I had been thinking a fair amount about identity myself before beginning this novel I did find it fascinating; there were a number of those moments of recognition when a novel describes a thought, a feeling, a sensation and you realise that you are not alone in what you feel. Doris Lessing's descriptions of Anna's sessions with her therapist and of her time of disintegration, are vivid and the latter time becomes immersive, drawing you into Anna's world, it is powerful writing. While Anna's notebooks, culminating in the final golden notebook of the title, are her way of working out her own identity and what she should do next, having published this successful novel and had a long, ultimately unsuccessful affair.

I have written all this and yet hardly touched on the themes, ideas and people of this novel, nor done the novel remote justice. The Golden Notebook has to be one of the most thought provoking, absorbing books I have read in years and although its length may seem daunting at first I would recommend making the effort. As time went on I found that I could lose hours to the book and that I became deeply engaged with what happened to Anna and loved the "Londonness" of the book - certain writers capture London so well. While doing a little research to write this I have found The Golden Notebook Project, a website containing the novel and the debate a number of female writers are carrying on in the margins, with space for further debate in a forum, which might be an interesting way of reading it. Lessing's own preface is on there too, although I am glad that I had not read it before I tackled the book, I prefer to make my own impressions, then read the introduction or preface to novels. The audio book I listened to is available for download here - it is very much cheaper if you join Audible and buy some credits - and I very much recommend the reading, an excellent option for knitters or other crafters.

Perhaps this coming month I will read something that does not concern feminism?

All the other posts from A Year in Books can be viewed here

Labels:

bookclub,

books,

feminism,

mental health,

the year in books,

war,

women

Saturday, 31 May 2014

The Year in Books: May

Yet again I have left it until the very end of the month to write this, procrastinating and not getting around to things as usual. Anyhow, here goes: this month's book is The New Woman: An Anthology of Writing by Women, 1880-1918, edited by Juliet Gardiner. The anthology begins by defining how, “the 'New Woman'... with her demands for

education, economic independence and sexual equality – and soon for

the vote – offered a challenge and a threat to the established

order” and outlining the debate surrounding the term.

Next the anthology turns to a discussion of

education, which was (and is) a vital building block of progress for women and what the

purpose of women's education should be: would it make her

discontented with a married life of domesticity? This question of

education also impinged on marriage and the expectations brought to

marriage. As Sarah Grand wrote in her 1888 novel Ideala:

“The girl has been taught to expect to find a guide, philosopher and friend in her husband. He is to be head of the house and lord of her life and liberty, sole arbiter on all occasions.”

But many women found that this was not so, how

could it be? The same piece goes on to discuss the need for an

equality in marriage and makes the wonderful comment that once women

have secured higher education for themselves they should work to

secure it for men! Many of the writers condemn the economic

dependence in which marriage placed women and the problems faced by

those who did not or could not marry. In order to pay men a “family

wage”, women's wages were generally half that of men's wages,

meaning that “the wages paid to women were barely sufficient to

sustain independent life”. The Women's Dreadnought records

in October 1924 that qualified women typists and bookkeepers could be

expected to work for as little as 4 shillings a week, meanwhile

other women engaged in war work could earn as little 6 shillings a week working ten

hours a day, six days a week plus overtime.

Students in a lecture at the Royal Free Hospital in London

Naturally there is a long section on the fight for

the vote, but what this book illuminated for me was that what the

women of this period were fighting for was much more than just the

vote. I studied women's rights in history lessons at school but the

late Victorian and Edwardian period was viewed solely in terms of

“Votes for Women”. This book demonstrates that these women were

fighting for rights in every field of life, true the vote was

crucial, so that women could no longer be “safely neglected” by the male Parliament and have a say in the laws

being passed, but the suffrage movement was part of a wider movement

to bring women education, equality, respect and freedom. This

anthology does what any good anthology does, introducing the reader

to a wide range of voices, some familiar, some new, around a subject,

providing insights and debate; I most highly recommend it. It is not all serious, there are some moments of levity, such as Ethel Smyth's account of learning to bicycle on the gravel sweep outside Lambeth Palace and teaching the Dean of Windsor how to ride. I exhort

the publishers to re-issue this book, because it is an excellent read and because the issues discussed

within it are sadly still relevant, as is shown by websites such as

Everyday Sexism. It is still available second hand mercifully, I came across it in our local library, the place I have discovered so many of my favourite authors.

I leave you with this forceful argument about the

very nature of woman and an interesting counterpoint to Rudyard

Kipling's famous poem.

If, after four or five generations of freer choice and wider life, woman still persists in confining her steps to the narrow grooves where they have hitherto been compelled to walk; if she claims no life of her own, if she has no interests outside her home, if love, marriage and maternity is still her all in all; if she is still in spite of equal education, of emulation and respect, the inferior of man in brain capacity and mental independence; if she still evinces a marked preference for disagreeable and monotonous forms of labour, for which she is paid at the lowest possible rate; if she still attaches higher value to the lifting of a top hat than to the liberty to direct her own life; if she is still untouched by public spirit, still unable to produce an art and a literature that is individual and sincere; if she is still servile, imitative, pliant – then, when those four or five generations have passed, the male half of humanity will have a perfect right to declare that woman is what he has always believed and desired her to be, that she is the chattel, the domestic animal, the matron or the mistress, that her subjection is a subjection enjoined by natural law, that her inferiority to himself is an ordained and inevitable inferiority. Then he will have that right, but not till then.

From Marriage as a Trade (1909) by Cicely

Hamilton

As an after note, knitters may find the following

poem interesting, although I do not entirely agree with the

sentiment, it reminded me of Kate Davies' posts about images of knitting.

Oh it's you that have the luck, out there in blood and muck:

You were born beneath a kindly star;

All we dreamt, I and you, you can really go and do,

And I can't, the way things are.

In a trench you are sitting, while I am knitting

A hopeless sock that never gets done.

Well, here's luck, my dear – and you've got it, no fear;

But for me... a war is poor fun.

Rose Macaulay, 1915

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)