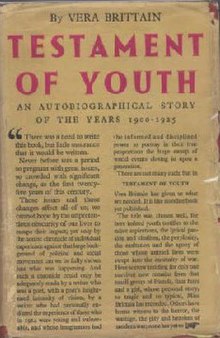

During the commemorations for the centenary of the First World War last month I decided that I should re-read Vera Brittain's memoir Testament of Youth sooner rather than later. There was, of course, the usual trepidation one feels when approaching a book one first read as a teenager, but I am happy to say that it has more than held up to my memory of it as a magnificent book. Vera Brittain left Somerville College, Oxford after one year to serve as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse (or VAD) during the war and the book covers her life from her birth in 1893 until 1925, when she married. Testament of Youth is particularly valuable in giving an impression of the state of mind of the British in the run up to the war, throwing some light on why it was such a cataclysmic event and so very shattering to those who lived through it.

The first clue to this is given in the preface written by her daughter, the politician Shirley Williams, who writes that one reason we are so haunted by the war is, "the total imbalance between the causes for which the war was fought on both sides, as against the scale of the human sacrifice". Brittain's account of the parts of the line, in the early part of the war, where neither side could see the point in killing one another and so had a small voluntary truce, shooting into the air and no man's land, is just one illustration of this point. Why this war in particular has caught our collective imagination and is such an important part of our collective story is a question I have often pondered. Our collective remembrance of war is still, a century on, so strongly shaped by the First World War, with our Remembrance Day poppies and our misty-eyed reading of Rupert Brooke and "age shall not weary them".

Brittain's book is a true help to understanding this question, by providing a solid pre-war background she is able to show how shattering the war was to her generation. There seems to have been a deep complacency and belief in progress, running alongside a belief in the spiritual good of war, testing us and even (in a way that would seem shocking to a post-1945 audience) purging the population. Brittain's account of attending speech day at her brother's public school in July 1914, with its military manoeuvres, shows the incredible militarism of the pre-war public schools, whence came most of the politicians and leaders of Britain. The Arnoldian* curriculum of Officer Training Corps, sport and extensive study of Classics** lent itself to a romanticised, spiritual view of war; it is after all a small leap from the Pass at Thermoplyae to the poetry of the early part of the war. However, these ideals failed to live up to the realities of trench warfare where death came at random from a shower of shells and bullets, killing indiscriminately the strong with the weak.

Testament of Youth has more than lived up to my teenage memories, it is an epic read, but not only is it worth reading, it is engrossing, so that you do not realise that you have somehow read a hundred, or two hundred pages. According to the biography of Brittain at the beginning of Testament of a Generation (a collection of her and Winifred Holtby's journalism) she found the book extremely hard to write, but I am immensely glad she persevered. I cannot recommend this book enough, do go and read it, it will enrich your understanding of the First World War immeasurably, but you will also spend time in splendid company.

Incidentally, reading Testament of Youth alongside Testament of a Generation has provided an interesting counter-point and each has cast some light on the other. Aside from the impression that feminism has not advanced that far from the 1920s and that in politics little changes, each book has provided flashes of insight that have illuminated aspects of one another. I was particularly interested to read an article discussing, in 1929, calls for the abolition of Remembrance Sunday, some apparently feeling that 11 years was quite sufficient to have remembered the war. Likewise her horror at finding her children's nanny fixing a poppy on baby Shirley's cot for Remembrance Day throws light upon the gulf Brittain felt between her generation and the one that followed it; for her the poppy was a symbol of war and grief, but for her young nanny it was another "flag day" like any other.

You can see the rest of The Year in Books entries here

*Dr Arnold of Rugby School, whose reforms set the pattern for public schools in the 19th century and whose influence is still felt today, cf. Tom Brown's School Days

**Many of the texts studied were decidedly martial in flavour such as Homer, Thucydides and Caesar

Like you I haven't read Testament of Youth since my youth, which must be remedied I think. Thanks for this post, I really enjoyed it.

ReplyDeleteThank you, she also answers some of the questions you were asking ages ago about why there was so much poetry written during the war and the novels came later. She says numerous times that she found comfort in poetry that she couldn't find in fiction, but also that reading fiction was an escape, but one that was hard to bear when you had to re-enter real life again and she found it too hard.

ReplyDeleteI have heard of this book, but never read it. Thank you for this wonderful insight into the book, you have inspired me to go and find a copy to read.

ReplyDeleteHave you read The Daughters of Mars? I was planning on Testament of Youth and spotted that newer book. I thought it well-done, but still plan to re-read Brittain.

ReplyDelete